On June 23, 2016, Emma O’Sullivan spent the evening in her apartment in the Gràcia district of Barcelona, initially concerned and later shocked by what she was hearing on the BBC: that 52% of her fellow Brits had voted to exit the European Union, leaving her and around 1,300,000 more British nationals living in the EU in a state of limbo.

“After the initial shock, I went through all the stages of mourning,” she recalls. “Denial, fury, resignation…” In fact, according to the Kübler-Ross model for dealing with grief, the third phase is bargaining, and this is essentially what Emma did; she negotiated her own exit from Brexit.

Fortunately, her grandfather on her father’s side was originally from Cork, allowing her to claim Irish citizenship. Michael O’Sullivan emigrated to London in the 1930s to finish his medical studies and ended up marrying an English nurse, Norah, which kept him in the UK where he had seven children, went to Mass every Sunday and died of a heart attack in 1964, seven years before Emma was born.

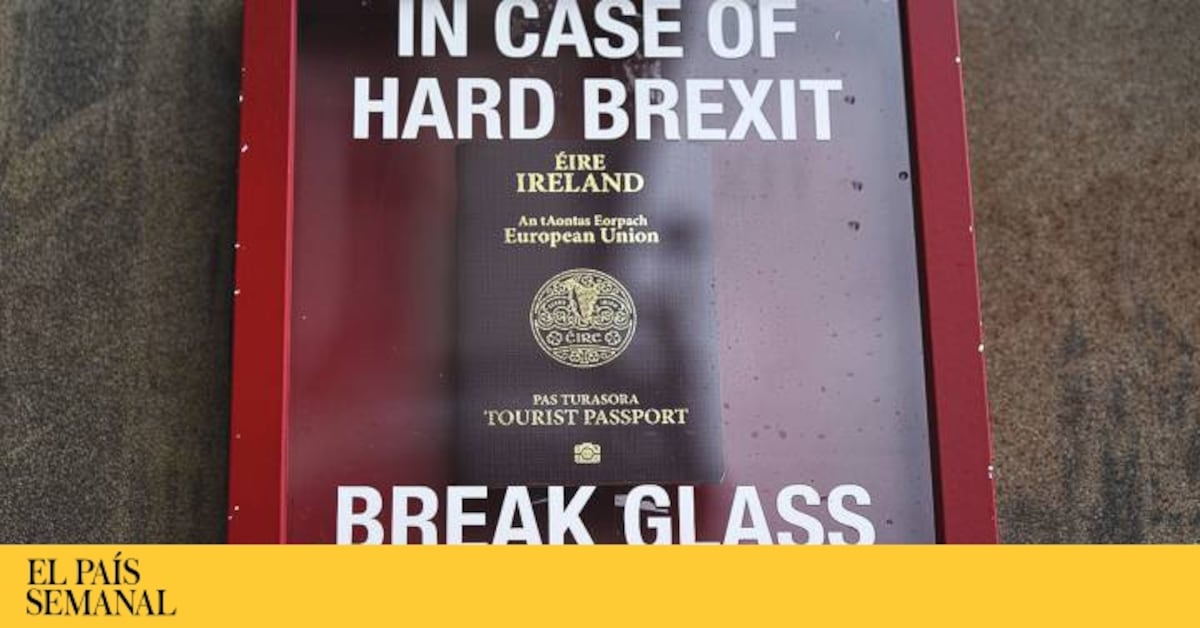

After many months of red tape, compiling documents and gathering certified copies, Emma has been able to officially declare herself a citizen of the Republic of Ireland, despite the fact that she has never set foot on Irish soil and still hasn’t got her passport.

“When I get my new passport, I should fly to Cork and kiss the ground like the Pope,” she jokes.

Another seven of the 15 O’Sullivan cousins have applied for Irish nationality. For most, it amounts to a political gesture rather than a necessity, but the fact that October 31 – the date earmarked for Britain to leave the EU – is looming makes it unlikely they’ll get it prior to Brexit.

The fact I have never had to think of my nationality before is proof of my white western privilege

Emma O’Sullivan

Before the referendum, Ireland’s Foreign Affairs Department was dealing with around 6,000 applications for citizenship a year. But in 2018 alone, it received 25,000. Irish civil servants involved in processing them have been snowed under, just one of the Brexit-related problems likely to be faced in a country where, after the third pint, the subject of Britain’s “800 years of oppression” tends to crop up.

Ireland and Great Britain both allow dual nationality, which is not the case in all EU countries. “I imagine that if I had had to drop my British nationality, I would have done so for practical reasons, but it would have meant more than a procedure,” says Emma, who has lived in Barcelona since 2006 and has no plans to leave.

“I’ve never been a nationalist,” she adds. “But this process has made me understand that there are certain things that are intangible. Basically, the fact I have never had to think about my nationality before is proof of my white western privilege. I’m not exactly fleeing from conflict with my belongings in a suitcase.”

In the process of becoming Irish, she has learned a number of things about her family as well. For example, she had an Irish great-aunt, Michael’s sister, who was so fiercely anti-British that she sympathized with the Nazis during World War II and went to live voluntarily in occupied France. This woman would undoubtedly find it extraordinary that 70 years later, eight of her very English great nephews and nieces are trying to become Irish.