Each October 12 Spain marks its National Day or Dia de la Hispanidad with a public holiday.

The day coincides with celebrate Christopher Columbus’ first voyage to the Americas, 529 years ago today, which is why it is celebrated in the USA where they call Columbus Day.

Back in Spain it is also known as National Armed Forces day, it is celebrated with a huge military parade in Madrid and air force planes painting Spanish flags across the country’s skies.

The army, navy, air force, Guardia Civil and even the Spanish Legionnaires, accompanied by their mascot goat – march down the capital’s Paseo de la Castellana watched by the Royal family, and Spain’s leading politicians.

But it’s not just Madrid that the event is celebrated. Malaga hosts a military procession, while Huelva holds a celebration and in Zaragoza a fiesta takes place dedicated to Our Lady of the Pilar, the patron saint of the Spanish Guardia Civil and the Hispanic world.

So why celebrate Columbus?

Anyone not in the know would be forgiven for thinking the great 15th-century explorer was Spanish.

But although Columbus’ true origins are the subject of much conjecture, it is widely believed that he was Italian, born in Genoa. So why is he so adored here?

Then, as now, it came down to ‘enchufados’ – his connections.

In 1485, following the death of his wife in Portugal, Cristobal Colon, as he is known here, moved to Palos de la Frontera in Huelva with his newborn son Diego.

He had been searching for a sponsor to finance his new transatlantic voyage, aimed at forging a westward sea passage to ‘the Orient’ (Asia).

Settlers planned to start a colony where they could convert people to Christianity and exploit the production of spices and other natural resources.

But the explorer was struggling to convince monarchs in Europe that such a route was feasible.

After asking the French, the Portuguese and even sending his brothers to seek support from King Henry VII of England, he finally won royal patronage from Spain’s King Fernando and Queen Isabella.

And all thanks to the prior of the Dominican convent of La Rabida in Huelva, where Columbus had been staying.

Father Juan Perez, who also happened to be Queen Isabella’s confessor, was impressed by Columbus and his plans. He convinced the queen to influence the king, and the explorer was called to court to re-present a proposal they had already rejected once.

The explorer demanded the hereditary positions of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and Viceroy and Governor of any lands he found, granting him a percentage of all revenues from new territories. After rejecting him once more, the Spanish monarchs reconsidered and agreed.

Before departing in August of 1492, Columbus pledged allegiance to the Spanish crown at the Convent of Santa Clara in neighbouring Sevilla. To this day this architecturally outstanding national monument remains a place of pilgrimage for tourists for its Columbus connection.

The Monastery of Santa Clara in Moguer, Huelva, also has special significance.

Abbess Ines Enríquez was King Fernando’s aunt and supported the voyages of Columbus. The explorer later spent a night at the monastery to fulfill a vow made at sea when a storm was about to capsize the Niña ship.

Columbus did a lot of praying, as any sail ship captain would in those mapless days. Before his first voyage, he visited the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de la Cinta, on the outskirts of Huelva city, to ask the virgin for her blessing. Highly revered by Columbus and his crew, he promised to revisit her on his return. The white-washed sanctuary is still standing today on El Conquero hill and continues to attract tourists.

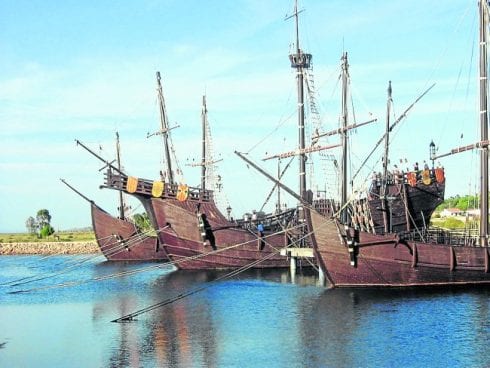

Having made his peace with God, a confident Columbus set sail from Palos on the Santa Maria (recently discovered) alongside the smaller ships Pinta and Niña. Replicas of this famous nautical trio can be toured today. Hardly transatlantic liners, you’ll be amazed how cramped they were.

What Columbus thought was Asia was in fact the Bahamas. He named the first island he discovered San Salvador, before reaching Cuba and Hispaniola where La Navidad settlement was founded with permission from the indigenous people.

Columbus returned to a hero’s welcome in Spain. Along with gold for the royal coffers he paraded the curious novelties he had discovered on his voyage: not only the tobacco plant, the pineapple and the turkey but the islands’ native people – also regarded as mere commodities and sold on as slaves.

He set sail again in September 1493 with a fleet of 17 ships, exploring the Caribbean and revisiting La Navidad, where a new settlement had to be founded because the men he had left behind had all been killed.

Hundreds of indigenous people were enslaved and many died on the return journey.

On his third trip in 1498, Columbus discovered Trinidad and Venezuela and plunged deeper into South America.

Still convinced he was visiting Asia, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, he returned to Spain and was made Viceroy and Governor of the Indies.

Accusations of tyranny and incompetence lead to his downfall. In 1500, he and his brothers were jailed for alleged atrocities against the native populations.

Columbus was released in time to set sail on a fourth and final voyage in search of a westward passage to the Indian Ocean.

Again he fetched up on the other side of the Atlantic, this time reaching Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama before being beached in Jamaica, where he and his crew were stranded for a year.

The explorer returned to Spain for the last time in 1504 and died two years later in Valladolid, at the age of around 54. The house is now a museum dedicated to his discovery of America.

Still convinced he had reached the Indies, but stripped of his governor titles and denied the profits from his New World discoveries, he died a disappointed man.

He would be pleased to know that he is held in far higher regard today, with his own national holiday in Spain.

And while everyone will make the most of a bank holiday and turn it into a ‘puente’ with an extra aday off to bridge the weekend with Oct 12, there is a growing movement of protest against the day, seen by many as a celebration of Spanish colonialism.

Some argue that marking Columbus day is an outdated celebration of the genocide that followed his discovery of “the new world”, while others still associate the military processions on the day as a hangover of Franco’s regime when it was used to demonstrate the dictator’s military might.

Those in Catalunya who support independence for the region are also critical of Spain’s National Day, Many town halls as well as companies refuse to observe it and instead swap the day off work to October 1, to mark the anniversary of the independence referendum.

READ ALSO: