POET Federico García Lorca was murdered on August 18, 1936, during the first stages of the Spanish Civil War. He became a martyr and a legend. The most translated poet in the Spanish language, his work is venerated wherever it is read. However, there are still aspects of his life that are not very well-known. One of them is his connection with la Alpujarra.

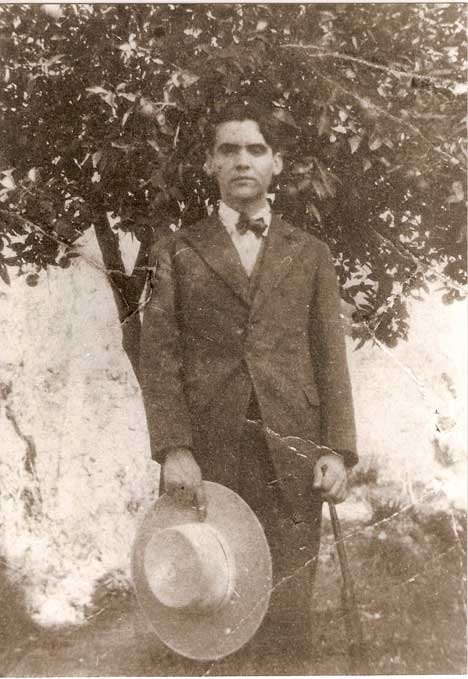

Earlier this year, the council of Pitres erected a monument in its main square commemorating the visit Lorca made to the village in 1932. It consists of a photograph of Lorca standing in front of a Y-shaped tree and an extract of a letter to fellow poet Jorge Guillén, which reads in part: “Here I am in Pitres, a village with no voice, or pigeons from the mountains, crucified on the Y of the tree.” It is hard to know what to make of this remark.

The presence of Lorca in la Alpujarra is a matter of some uncertainty as he did not write much about the mountainous region. But there are a few letters, postcards and photographs that prove he was a regular visitor until 1934, two years before his tragic death.

‘Admirable’ Lanjaron

His first contact with the area was with the spa town of Lanjaron, the gateway to la Alpujarra. Federico’s mother, Vicenta Lorca, was ill with a liver condition and a doctor prescribed a treatment of water from the town’s Capuchina fountain, famous for its curative properties since Mozarab times.

Therefore from 1917 until 1934, the Lorca family spent a few weeks every year in Lanjaron at the Hotel España, which stands to this day.

Federico’s first written testimony about Lanjaron that has survived is a postcard dated August 17, 1924, to the Cuban diplomat and poet Melchor Fernández Almagro. “What an admirable place. You should come to visit this paradise. I have found curious romances and tales.”

At this time, Lanjarón was a meeting place for Granada’s bourgeoisie and intelligentsia. After bathing in the town’s many spas in the morning, the afternoons were dedicated to walks and excursions. One of Federico’s favourite places was Lanjaron’s Moorish castle and he posted numerous postcards of it. In one of them, sent to the critic Sebastian Guash, he describes Lanjarón as: “Sierra Nevada, which means that you are in the heart of Africa, at the entrance to la Alpujarra. The most incredible fantasies develop in the most serene and logical way.”

During his holidays in Lanjarón, Federico had a busy social life. One activity he enjoyed were the regular excursions to the nearby sierras with one of his best friends, the priest Juan Padial, who showed him the beautiful Castaño Gordo and the Barranco de las Adelfas. There on top of the mountains the view on clear days was incredible; the sea lay in the distance with the mountains of Africa beyond and below was the vega de Lanjaron, cultivated with cereal, fruit and olive trees, all irrigated by the network of acequias (irrigation channels). In a letter to artist Sebastian Guasch, Federico writes: “In Lanjarón, oh mountains! Oh orange trees! I am reborn to your friendship.”

But the poet also had time to work and to find inspiration in the manner people talked. For him, they are the descendents of the Moriscos. “No doubt that here the nostalgia is anti-European, but it is not oriental. [It is] Andalucia.”

In the evening, after a long day, there would be a dance in a salon of the Hotel España and Federico would play the piano.

Inspiration

Lanjarón acted as a base for Federico and his excursions deeper into la Alpujarra. In the 1920s, Federico was an assiduous participant of one of Granada’s most famous gatherings, El Rinconcillo, which took place in the café Alameda. The participants were some of Granada’s leading intellectuals. One of the most famous was the musician Manuel de Falla, who soon made friends with Lorca as they were both interested in folk music.

In 1922, Federico wrote a letter to Falla mentioning la Alpujarra as a wonderful place to search for old folk songs. “Maybe we could take the Cristobicas to its villages,” said Federico. Las Cristobicas was a puppet show for children.

Lanjaron and la Alpujarra influenced Lorca’s work and, while he was there, he wrote and edited poems such as La casada infiel, Reyerta, Reyerta de mozos and San Miguel. While in the mountains, he also made a great number of drawings.

Federico was also inspired by places like Órgiva, where Falla loved talking to the people and getting lost in the streets. Lorca describes Órgiva in a letter to surrealist painter Salvador Dalí as “a myth of fresh water in a glass of pure crystal.”

The most important testimony from Lorca’s excursions to la Alpujarra is a letter to his brother Francisco, who lived in Paris at the time. Federico was invited in 1926 by Manuel Segura, a professor of law in Granada, on a two-day excursion to the region. “I did a little excursion to la Alpujarra. It took us two days. I have never seen anything so exotic and mysterious. I can’t believe that it is in Europe.”

But he also saw the dark side of the villages, the Guardia Civil often ruled their inhabitants with cruelty and brutality, especially the gypsies, a race Lorca respected and loved for their flamenco culture.

He had heard that a Guardia Civil had pulled out with some pliers the teeth of a hungry gypsy who had stolen a hen.

Maybe these stories inspired one of his most famous poems, “El romance de la Guardia Civil” or “Canción del gitano apaleado.”

However, the blacker aspects did not stop him from glimpsing vivid scenes, which he describes in the letter to his brother. “There are two perfectly defined races: the Nordic and the Morisco. I saw a Queen of Sheba shelling corn against a wall of purple colours and I saw a Child King dressed as a barber.”

Travelling with Falla in the search for folk songs, Lorca visited the villages of Carataunas, Soportujar, Pitres and Haza del Lino. But there is another area of great importance.

According to the writer and journalist Rafael Gómez Montero, at Christmas 1926, Lorca stayed in a cortijo close to the hamlet of Bayacas. Lorca biographer Ian Gibson also mentions this excursion.

Cortijo Montijano was in an area of Bayacas known as ‘Pollo Dios,’ between Carataunas and Órgiva. The Sortes Cave, which was inhabited by gypsies, was also nearby.

One night, after dinner, Federico and his friends listened to some coplas sung by the son of the caretaker of the cortijo. One of the songs about infidelity immediately caught their attention: Que yo me la llevé al río, creyendo que era mozuela, pero tenía marío.

Lorca was challenged by his friends to write something inspired by this copla. From this he produced La Casada Infiel, which became part of the Romancero Gitano.

In the poem, Lorca describes the Río Chico that runs down from Soportujar and Cañar and joins the Guadalfeo river, and one of the protagonists was a gypsy that lived in the Cueva de Sortes.

Over the years, la Alpujarra has exerted an attraction on many people and Lorca’s letters, postcards and photographs show that he was also under its spell.

Not only was he attracted by the landscape, but the people and their culture. A large part of his visits to the region will probably always remain obscure due to the lack of material. If he had lived perhaps he would have written something more substantial about the area.

The Olive Press would like to thank Juan Gonzalez Blasco, Carmela de Luna, the Manuel de Falla Archive and the Federico Garcia Lorca Foundation

Antonio de Luna, Manuel de Falla, Federico García Lorca and José Manuel Segura (from left to right) stand flanked by children in Órgiva.

For many years, Harvard University believed this photograph depicted Lorca and de Falla in Guadix during the summer of 1926.

However, the Olive Press can reveal it shows the pair in Órgiva. As local historian Juan Gonzalez Blasco asked: “Why would they be wearing heavy overcoats and scarves in summer in Guadix? This photograph was taken in La Alpujarra – Órgiva to be precise – in what is today Plaza Jiménez e Iglesias.”

To further his claims, the photograph was ceded to the Olive Press by Carmela de Luna, whose father appears in the photograph.

This photograph was taken during an excursion into the mountains of La Alpujarra in February 1918. Lorca is seen standing in front of an orange tree at 2,000 metres above sea level.

On the back of the photo, the poet wrote: “I am sure they wanted to take a photograph of me in a panama hat with a rifle in my hand. Orange tree situated at 2,000 metres altitude. I can see from here Soportújar, Laujar, Vallacas [sic], Cañar. I can hear the song of four rivers that give water to the olive trees of the vega.”