CAMPAIGNERS are calling for recognition of a shameful period in the history of Madrid’s Retiro park when people would come to stare wide-eyed at live exhibits in a ‘human zoo’.

When news came through last month that Madrid’s Retiro Park had been awarded with the coveted World Heritage Site status, it was greeted with celebration across Spain.

At last Madrid’s leafy oasis in the centre of the capital with its rose garden, boating lake and lofty glass exhibition hall had been given the recognition it deserved.

But, for some the news came as an opportunity to explore the history of the park, and with it calls to make amends for a shameful episode that blights the Retiro’s past.

Towards the end of the 19thCentury, Madrileños flocked to the Retiro Park not just to enjoy a stroll beneath the shady boughs of its many trees but also to gawp at a rare exhibit that had been shipped in from a far-flung corner of the Spanish empire.

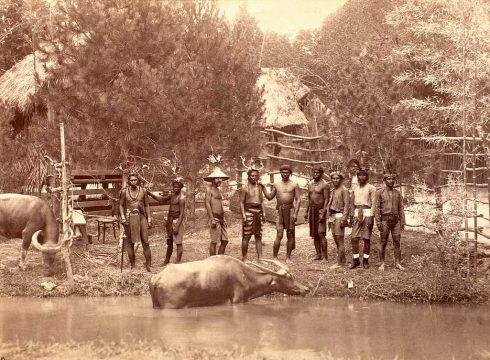

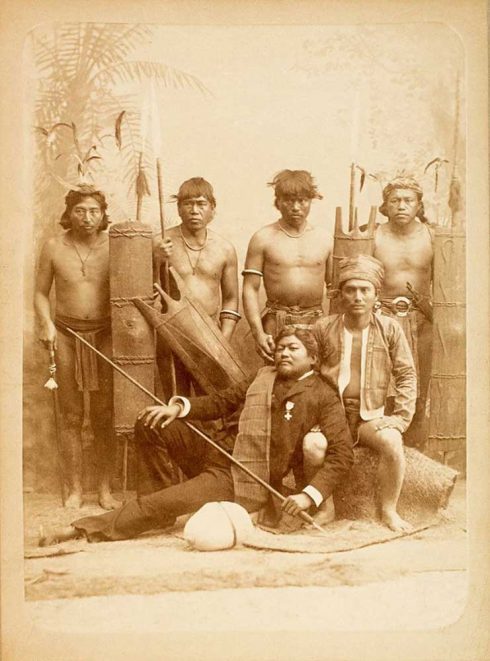

Alongside the Palacio de Cristal, a colossal greenhouse built to contain tropical plants from across the Philippines, was a replica village, a model of the sort of settlement found on the Filipino island of Luzon.

Housed within it as the centrepiece of the exhibit were 43 Igorot men and women brought from the other side of the world to play out their lives in front of curious onlookers.

In April 1887, the Exhibition of Philippines, then a part of the Spanish empire, was inaugurated by Queen Maria Cristina.

During the next six months tens of thousands from across Spain came to gaze at the prize exhibits in their folk costumes as they carried out their ‘typical’ daily activities of hunting with spears, fishing from wooden dugout canoes or ploughing the land with oxen.

Records show that at least four of the Igorot people brought over died as a result of poor living conditions during the exhibition, but apart from a few photos hidden within city archives, there is no public acknowledgement of their plight on public display.

All that remains to inform curious visitors today is a small weather-beaten plaque outside the Crystal Palace that names the architect and the dimensions of the structure and what plants were originally contained within it. No mention is made of the human exhibits.

Leah Pattem, an amateur historian wrote about the shameful secret history of the Retiro human zoos in her blog Madrid No Frills that has been shared by thousands.

“It took me three visits to the National Museum of Anthropology to find any acknowledgment of the people involved in the 1887 exhibition. On a small display card beneath the boats, a sentence reads “…city residents could ride in them with the aid of the Filipino crews”. Other than this, you have to dig deep into the museum’s archives which are not accessible to the public,” she told the Olive Press.

Campaigners now want the true history to be told as a way of putting the racist world view of the past into context for modern times.

“The point of UNESCO is to preserve and protect, through education and culture, a universal respect for human rights,” explained Alexis Lahorra, a Madrid-based Filipino Canadian activist, who has taken up the cause, in an interview published in gal-dem.

“Why is it that we’re not protecting the people who were in the exhibition? Their dignity was taken away. By remembering them, we can at least try to recover some of that.”

Fellow activist Angelica Pfleider, also from the Philippines, insists that historical wrongs shouldn’t be buried.

“Acknowledging the human zoos in Madrid’s Retiro Park will show other racially marginalised groups, such as Roma people and Indigenous Latin Americans in Spain that it’s also possible to acknowledge what was done to them in the past,” insisted fellow Filipino activist Angelica Pfleider.

“If we’re successful, it could give others the courage and inspiration they need to seek the truth about their own history too,” she said.

Pattum adds: “It seems clear to me that the inclusion of 43 Igorot people in the Exhibition of the Philippines has been deliberately omitted because historians are aware that this is a shameful episode in Spanish history. However, we must confront and acknowledge Madrid’s human zoo because, if we don’t, it’s as good as saying what happened was ok – a passive action which has a direct consequence on racist attitudes and behaviours today, in Spain and beyond.

“There are many more monuments in Madrid with hidden racist histories and we hope that updating the plaque outside the Palacio de Cristal will pave the way for further updates to be made around the city.”

READ ALSO: