If you have walked through Puerta del Sol square in downtown Madrid, you may have seen them. Among the people dressed up as Super Mario and Mickey Mouse, the cigarette stands and the buskers, they slip in and out of the crowd, often approaching passers-by with signs asking for money.

Most people overlook them. Not Michael Damanti. To this American street photographer, they are not “just Gypsies,” they are women with stories, names and families. They are his friends.

When Damanti arrived in Madrid six years ago with his wife, who is from Spain, and their two small children, he was not planning on becoming an advocate for Madrid’s Roma community. But as he passed the women on his way to work each day, he became increasingly curious about them.

But when Damanti asked the people in his office about them, the response he got was: “‘Oh they are just some Gypsies. Stay away from them. They’ll rob you, they’ll spit on you, they’ll surround you and pick your pocket. They’ll take a knife and cut you,’” he explains. “I would watch them every day and I didn’t see any of that.”

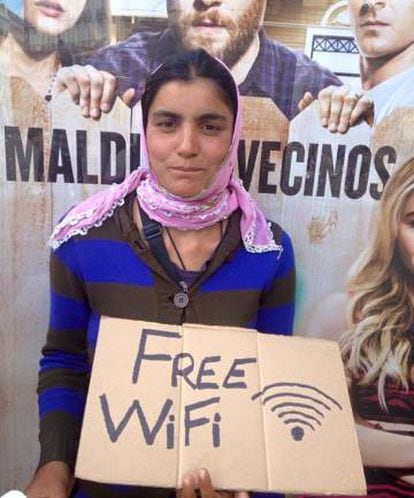

So Damanti decided to approach the women for himself. He noticed that no one was reading their signs, and decided to create his own. Instead of the long, four-line messages asking for money, Damanti’s signs said things like “Free Wi-Fi,” “Does it even matter what this sign says?” and “#Brexit Keep calm and give me money.” He offered them to the women, who were suspicious at first, but quickly realized the light-hearted signs were more effective.

From then on, Damanti began getting to know the women, and they allowed him to take their photos. At that point though, Damanti – who was working for Getty as well as a sales company – just thought of the women as “photographic gold.”

“I approached it from a purely photographic standpoint from a distance. I don’t know them, they don’t know me. I’m just taking photos,” he explains.

There is an accepted amount of racism towards them that nobody disputes

Photographer Michael Damanti

But this professional distance collapsed the day that one of the Romani women, Sibella, was rushed to hospital to have an emergency C-section. Damanti was walking to work when the Gypsy women found him and told him what happened – Sibella had had the baby but the hospital wasn’t going to let her keep the child because she had no Spanish address. The hospital could not “release a baby to go to the park to sleep on the ground,” he explains.

Suddenly, the photographer found himself talking to staff at Moncloa hospital, looking up Roma support groups on LinkedIn and tracking down Sibella’s husband in Madrid’s Plaza de España square.

He found out that Sibella would be able to keep her baby if she could provide an address in Romania, proof of a ticket, and photos for the family book. Thanks to his help, Sibella was able to keep the child. It was a turning point in his relationship with the women.

“Here I was this street photographer meant to keep my distance from the subjects and now I’m involved. It was impossible not to get absorbed into their lives,” he says.

Damanti began learning more things about the women: many couldn’t read, one elderly woman could not understand numbers, and surprisingly, they did not know their birth dates. Damanti also spoke to the Romani men, but communication was harder because they spoke no Spanish.

By looking at their Romanian ID cards, Damanti was able to find out the days they were born and introduced them to the concept of a birthday party – they didn’t know how to sing Happy Birthday or that you had to blow out the candles on the cake.

“In the course of a year or so, it went from these scary women and guys who were going to stab me and rob me to, ‘Let’s sit down and have an impromptu birthday party on the floor’,” he says.

But what surprised him most was the level of racism faced by the Romani community: “There is an accepted amount of racism toward them right here in a capital city in Europe that nobody disputes,” he says.

He’s seen an elderly Spanish woman spit at them and call them “parasites,” watched as an elderly man offered Sibella €5 for oral sex, and tried to help a pregnant woman named Sevda who had been punched in the face while she was sleeping by a drunken Spanish man.

The women can’t even go into a McDonald’s to buy an ice cream on a hot day without being manhandled out.

“I’ve never seen racism like that,” says Damanti. “It was like the racism you would hear in apartheid or pre-civil rights United States. It was blatant, screaming in your face ‘dirty fucking Gypsy, get out of here you whore…’

“All rules are off when it’s a Gypsy,” he adds. “And it has been happening for generations. They’re just used to being told that they’re a parasite.”

What’s more, no one else seemed to care. “I could sense eyes were rolling any time I told these stories. No one would listen,” he explains.

But Damanti couldn’t stand by and do nothing: “It would take an extremely stoic and sociopathic person to see all this and keep taking photos and then say, ‘I’m going back to work’.”

So he helps out in any way possible – be it bringing the women food or supplying them with second-hand baby clothes. But more than anything, he wants to show people that they are not “dirty Gypsies,” but people who smile, who laugh, who’ll make funny faces and share their food with you. His photos – which are always shot at eye-level – capture these unguarded moments and offer a rarely seen glimpse into their lives.

At an exhibition of his work this year at the Galileo Cultural Center in Chamberí, many of the visitors were surprised to see this side of the Romani community. Damanti was even asked to run private tours to explain the stories behind the photos. For Damanti, it was a baby step toward changing the negative perceptions of Romani people in Spain.

But there is a lot more to be done. The Roma community is still highly marginalized not only in Spain but also across Europe.

In Damanti, at least, the Romani community in Madrid has found an unlikely friend and ally. He says he is the lucky one: “They are the best thing to have happened to me in Spain.”