THE Battle of Jarama in February 1936 during the Spanish Civil War served as a brutal reality check for the anti-fascist volunteer army known as the International Brigades.

Most of the fighters lacked military experience, having been drawn to the war because of their political convictions, and attempting to hold back the professionally-trained Spanish army bolstered by troops from Germany and Italy proved deadly for many.

But one man from the American volunteer force, known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, did have military experience. 36-year-old Oliver Law, a veteran of World War I, impressed his colleagues with his skill and bravery in the battle.

Afterwards, he earned a promotion to commander of the brigade’s machine gun company.

And when the brigade’s commander Martin Hourihan fell ill, the soldiers turned to Law to lead them on. In just six short months, he had risen from soldier to commander, in doing so becoming the first Black American ever to lead integrated American troops.

Such a rise would not have been possible had Law been fighting with the U.S. military, which remained segregated until after World War II and barred African Americans from serving at the highest ranks.

Law was acutely aware of this discrimination. Born in Texas in 1900, he joined the U.S. army as a teenager, and fought in France during World War I. Although he stayed in the military after the war, he was prevented from rising beyond the rank of corporal.

So he left the army in 1925 and traveled north, ending up in Chicago. When the Great Depression hit, though, Law found himself unemployed.

Frustrated by the labor shortage and lack of government assistance during this time, he joined the local Communist Party, setting him on the path to fighting in Spain.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out, America and many other Western democracies adopted a non-interventionist policy. This left the Soviet Union as the Spanish Republican forces’ lone major ally, and they put out a call for volunteers across the world to come and fight.

Around that time, Law’s activism in the Communist Party involved protesting Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia under Mussolini.

So when he heard that these same forces were helping to assert fascism in Spain, Law, along with 2,800 other Americans, 90 of them African American, decided to fight back.

They joined over 30,000 men and women from 52 countries who made their way to Spain to form the International Brigades.

Law and his American comrades arrived in January 1937, and Law was made commander in June.

Unfortunately, he only held this position for a few weeks as he died just west of Madrid at the Battle of Brunete in July.

According to those who were with him, Law died as he fought: fearlessly.

Fellow soldier Harry Fisher explained that he ran across a hill, known as Mosquito Ridge, waving his men towards the enemy. “

He was the first man over the top… he [did not] attempt to protect himself, and in a matter of seconds, machine-gun fire ripped into him,” Fisher recalled.

The war ended two years later in defeat for the Republicans, but it was only the precursor for the coming international fight against fascism.

World War II saw the USA and the other western democracies officially enter the fray, ultimately succeeding in defeating Hitler and Mussolini’s forces.

Although Law and his colleagues were pioneers in this fight against fascism, the American government did not see them as heroes like those who fought in World War II.

Instead, those who made it back were treated with suspicion due to their communist leanings, and became targets of the FBI.

And although the city of Chicago recognized Law by declaring November 21st Oliver Law Day in 1987, he is still a largely overlooked figure in American history.

His legacy has faced a similar fate in Spain. During Franco’s reign, the government promoted a simplified story of the Civil War favoring the fascists, and the “pact of forgetting” instituted after his death meant the specifics of the war were largely swept under the rug.

While many on the left today celebrate the Brigades, those on the right have a less favorable view so it remains a contentious topic.

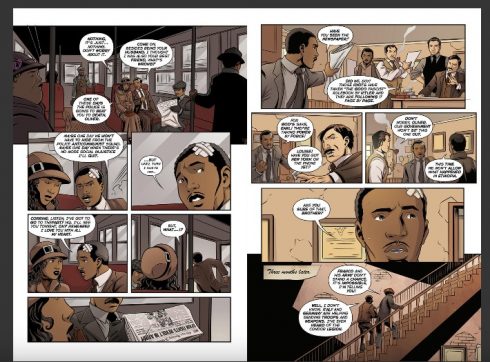

One author, Pablo Durá, has attempted to elevate the history, recently publishing a graphic novel telling the story of Law and the International Brigades.

He said, “if this graphic novel can help and play a small part in keeping the memory of those who came to Spain [to fight] alive, I’d be very happy.”

Indeed Law’s story is certainly one worth telling. As his fellow troop member Steve Nelson said at a celebration of their acts in Spain in 1986, “it is important that we recognise now that it was an historic moment – a Black man was placed in charge of a largely white unit for the first time in U.S. history. We want the world to share in the pride that we feel.”

READ ALSO: